Abstract

As a pharmacist in a country with 12 official languages, I started noticing how the incorrect use and misinterpretation of language used on prescriptions can cause potential serious harm to patients` health, and perhaps even death. For this article, we must acknowledge that medical staff from other countries with different languages, are living in South Africa and working in the healthcare sector. While I found several articles on prescription errors, there weren`t any articles I could find on language used on prescriptions. In this article, I explore some of the dangers associated with misinterpretation of prescriptions.

Introduction

A prescription is defined as an instruction written by a medical practitioner that authorizes a patient to be issued with a medicine or treatment.1 In my own daily life working as a pharmacist, I come across many examples of prescriptions written in one of our native languages: Afrikaans. Then I start to wonder how an assistant or pharmacist who does not have the ability to read or speak Afrikaans, and who might even be an immigrant, will interpret these prescriptions.

The aim of this study is to:

- make medical practitioners aware of the importance of using the correct language on prescriptions

- make life easier for medical personnel trying to interpret prescriptions written in a foreign language

- encourage comments and suggestions from the general population and medical personnel

- create an inclusive and safe environment for medical personnel where they can share their own experiences related to the subject, and discuss solutions

Methodology

Online research methods (ORM) were used. The author processes prescriptions as part of his work and used two of these prescriptions as examples to demonstrate the problem. This article is also presented as a blog post in an attempt to create a discussion on the topic and have, not only medical personnel, but also patients share their experiences, thereby assisting in further research.

Results

If a prescription is not written in an understandable language, it might lead to serious consequences for the patient. As medical professionals, we need to adhere to a universally understood language. We need to make sure that our patients get the best, safest and most effective treatment possible.

According to South African pharmacy law, the work done by a pharmacist assistant or intern must always be monitored by a supervising pharmacist.2 Once a pharmacist assistant or intern has finished interpreting the prescription and prepared the medication, it needs to be signed off by the supervising pharmacist before being dispensed to the patient. The supervising pharmacist needs to check that the correct medication was picked, the medication labels are correct, the directions on the medication labels match the directions on the prescription, the quantities of tablets, capsules, etc. are correct, and other clinical information that might be relevant.

Considering that many pharmacies in South Africa might not have personnel who can read, write or speak Afrikaans, we may have a very serious and potentially life-threatening situation requiring urgent attention.

Discussion

When students are trained to become doctors, pharmacists, medical assistants, nurses, optometrists, dentists, etc., they are introduced to Latin phrases and abbreviations commonly used on prescriptions. These Latin phrases are used as a universal language when writing prescriptions.

The following Latin abbreviations are sometimes used on prescriptions:3

- ac (ante cibum): before meals

- ad (auris extra): right ear

- ad lib (ad libitum): use as much as desired

- al, as (auris laeva, auris sinistra): left ear

- au (auris utraque): both ears

- bid (bis in die): twice a day

- cap, caps (capsule): capsule

- cf: with food

- daw: dispense as written

- dieb alt (diebus alternis): every other day

- emp (ex modo prescripto): as directed

- g: gram

- gr: grain

- gtt(s) (gutta): drop(s)

- IM: intramuscular injections

- IV: intravenous

- mdu (more dicto utendus): to be used as directed

- OD (oculus dexter): right eye

- OS (oculus sinister): left eye

- OU (oculus uterque): both eyes

- pc (post cibum): after meals

- po (per os): by mouth

- pr (per rectus): by rectum

- prn (pro re nata): as needed

- qad (quoque alternis die) or qod (quaque [other] die): every other day

- qam (quaque die ante meridiem): every morning

- qd (quaque die): every day

- qh (quaque hora): every hour

- qhs (quaque hora somni): every night at bedtime

- q3h (quaque 3 hora): every three hours

- q4h: every four hours

- q6h: every six hours

- qid (quater in die): four times a day

- qod: every other day

- qpm (quaque die post meridiem): every afternoon or every evening

- qwk: every week

- sc, subc, subcut, subq, sq: subcutaneous

- sig (signa): write

- tab (tabella): tablet

- tbsp: tablespoon

- tsp: teaspoon

- tid (ter in die): three times a day

- top: topical

- ud, ut dict (ut dictum): as directed

- w: with

- w/o: without

- x: times

If these abbreviations and phrases are used on prescriptions, any medically trained professional will know what they mean, and it would possibly decrease the risk of prescription misinterpretation. Yet, many prescribers do not adhere to the exclusive use of Latin phrases on prescriptions, with good reason. There aren`t, as an example, any Latin abbreviation to inform one of a certain allergy a patient might have. For this reason, many prescribers find it easier to write instructions in plain language.3 But the problem arises when the plain language used, is not English or a native language understood by the whole population.

What could possibly go wrong?

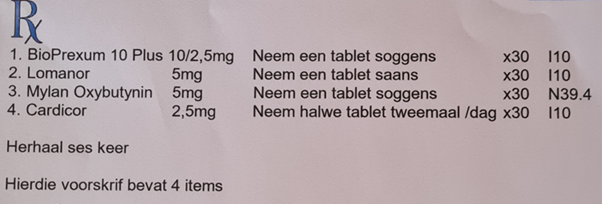

This is an extract of a prescription from a doctor for a patient who both understand Afrikaans as it is their native language:

Had the patient handed in their prescription at a pharmacy where none of the personnel understood Afrikaans, chances of prescription misinterpretation would have been guaranteed. What would probably have happened, is that the pharmacist, intern or pharmacist assistant who dispensed the medication, would have seen that 30 tablets of each medication were prescribed. As prescriptions, especially chronic prescriptions, are prescribed for a month and made repeatable for a variable number of months, the pharmacist or assistant would have made the directions of each medication: Take one tablet daily.

But these are not the directions stated on the prescription. The directions next to items one and three state that one tablet of each needs to be taken in the mornings. One tablet of item number two needs to be taken at night. Item number four is a bit more complicated: only half a tablet needs to be taken in the morning and the other half needs to be taken at a different time of the day, either in the afternoon or at night. Clearly, the desired outcome in treatment would not have been achieved.

To make matters more complicated, the prescription is made repeatable six times, which is also written in Afrikaans. In South Africa, chronic prescriptions are generally made repeatable for five months. However, some doctors make the prescriptions repeatable for four months or even less. The reason for this is that treatment might be experimental and a follow-up consultation with the doctor would be necessary to monitor the patient`s response to the prescribed medication. If the doctor had made the prescription in this example repeatable for only two months with the intention of potential dosage adjustments, the patient might have used the incorrect therapy for a total of six months. If one of the medications have had a damaging effect on the patient`s health, the doctor would have only noticed it after it was too late or if irreversible damage to the patient`s health had already been done.

Lost in translation

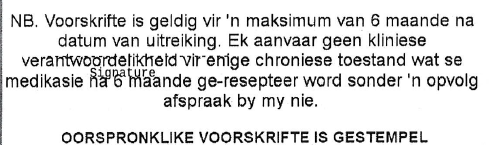

In the following example, which is an extract from a prescription written by an Afrikaans doctor, this clause was written at the bottom of the prescription:

It is an important note addressed to the pharmacist, intern or assistant dispensing the medication. In this clause, it states that prescriptions are only valid for a maximum of six months and that the doctor, therefore, takes no responsibility for any chronic condition after this period of time if any further repeats are issued without the patient consulting them first. It also states that original prescriptions are stamped. In other words, if this prescription was not stamped, and given to a pharmacist, intern or assistant who did not understand Afrikaans, it would have been an invalid prescription.

So, the question now is: How can someone who does not understand Afrikaans and who, perhaps, immigrated to South Africa from a country where they, as an example, only speak English and French, be expected to interpret this note? They can`t. Not without consulting another colleague who might be able to understand Afrikaans or phoning the doctor to confirm what was written on the prescription. Phoning the doctor has challenges of its own and is, most of the time, extremely difficult to do. The doctor might be unable to take your call, or there might be a line of patients forming inside the pharmacy, putting more pressure on staff.

Conclusion

Further research needs to be done, and an action plan needs to be formulated to make prescribers aware of this serious problem.

Funding

None

Conflict of interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Stevenson, A. & Waite, M. (eds.) 2011. Concise Oxford English Dictionary. 12th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Regulations related to the practice of pharmacy. [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.pharmcouncil.co.za/Media/Default/Board%20Notices/Regulations%20practice%20of%20pharmacy_Amendment2024.pdf

- Eustice C. Understanding Prescription Abbreviations [Internet]. 2024 Aug [cited 2024 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.verywellhealth.com/understanding-prescription-abbreviations-189318